Biology

Virtually all Christmas trees sold today are conifers. Conifers are plants with 1) cones, 2) aromatic resin, and most are 3) evergreen. Below is a description of these particular attributes that combine to make conifers so unique and well-suited to being such great Christmas trees.

1. Cones

Conifer is derived from the Latin conus (meaning "cone") and ferre (meaning "to bear"). These cones perform the same basic functions as the flowers and fruits of their distant cousins, the flowering plants — they are the sites of sexual reproduction and the production of seeds. Pollen is released by separate, smaller cone-like structures called strobili (STRO-bi-ly) and carries a plant's sperm to the immature female cone via wind currents. In particular, the pollen must reach small egg-shaped structures in the cone called ovules and then will release its sperm to fertilize the egg that is inside the ovule. As the fertilized egg develops into an embryonic Christmas tree, the ovule itself will enlarge and develop into the seed which houses and protects the embryo until the conditions are right for germination.

Conifer is derived from the Latin conus (meaning "cone") and ferre (meaning "to bear"). These cones perform the same basic functions as the flowers and fruits of their distant cousins, the flowering plants — they are the sites of sexual reproduction and the production of seeds. Pollen is released by separate, smaller cone-like structures called strobili (STRO-bi-ly) and carries a plant's sperm to the immature female cone via wind currents. In particular, the pollen must reach small egg-shaped structures in the cone called ovules and then will release its sperm to fertilize the egg that is inside the ovule. As the fertilized egg develops into an embryonic Christmas tree, the ovule itself will enlarge and develop into the seed which houses and protects the embryo until the conditions are right for germination.

Why are cones important? Quite simply, every single Christmas tree starts life in this way, as an embryo inside a seed inside a cone. The seeds of cones also are food for wildlife, and the seeds of pinyon pines of southwestern North America and the Mediterranean ("pine nuts") are enjoyed by humans.

2. Resin

Conifers are the quintessential symbols for a fresh, clean scent. That scent comes from

the volatile chemicals contained in the resin produced in resin canals that are unique to

conifers. These resin canals typically run throughout the entire plant, from the roots through the

stems and leaves. Resin is the sticky substance that oozes out when a part of a conifer

is cut or broken, and this resin serves the plant as something analogous to what a

first-aid antibiotic ointment does for humans — protecting the wound from harmful

infection. The primary constituents of this resin are the solvent turpentine and a waxy

solute, rosin.

Conifers are the quintessential symbols for a fresh, clean scent. That scent comes from

the volatile chemicals contained in the resin produced in resin canals that are unique to

conifers. These resin canals typically run throughout the entire plant, from the roots through the

stems and leaves. Resin is the sticky substance that oozes out when a part of a conifer

is cut or broken, and this resin serves the plant as something analogous to what a

first-aid antibiotic ointment does for humans — protecting the wound from harmful

infection. The primary constituents of this resin are the solvent turpentine and a waxy

solute, rosin.

3. Evergreens

An evergreen is a plant that has green leaves (in this case, "needles") all year. No one needle lasts forever, however: the life span of any one needle depends upon the species. A needle on a Douglas-fir, for example,

may last about eight years. You may have noticed, however, that even evergreen conifers experience an increased leaf-shedding in Autumn as the oldest, now-years-old leaves are shed at higher frequency during this season.

An evergreen is a plant that has green leaves (in this case, "needles") all year. No one needle lasts forever, however: the life span of any one needle depends upon the species. A needle on a Douglas-fir, for example,

may last about eight years. You may have noticed, however, that even evergreen conifers experience an increased leaf-shedding in Autumn as the oldest, now-years-old leaves are shed at higher frequency during this season.

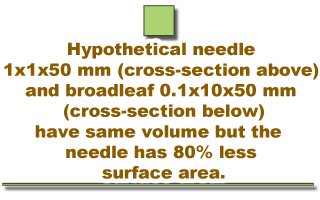

Needle-shaped or scale-like leaves help evergreens conserve water during dry winter months

Most plants in temperate climates lose their leaves in Autumn for two reasons. The first

reason is to avoid drying out. Plants lose most of their water through their leaves (the

flat, thin leaves of deciduous trees have an extremely high surface area-to-volume ratio).

Water is in short supply for plants during most temperate winters, both because the soil

water is often frozen and because precipitation is less. Furthermore, humidity is lower

during winter and the dryer air would cause the plant to lose even more water from its

leaf surfaces. Thus, many temperate areas are effectively "deserts" during the winter

months and the shedding of leaves is an adaptation for water conservation. The leaves of

conifers, however, are adapted to cope with limited water in the winter by (1) their

needle shape, which decreases the surface area-to-volume ratio, (2) their sunken stomata

Most plants in temperate climates lose their leaves in Autumn for two reasons. The first

reason is to avoid drying out. Plants lose most of their water through their leaves (the

flat, thin leaves of deciduous trees have an extremely high surface area-to-volume ratio).

Water is in short supply for plants during most temperate winters, both because the soil

water is often frozen and because precipitation is less. Furthermore, humidity is lower

during winter and the dryer air would cause the plant to lose even more water from its

leaf surfaces. Thus, many temperate areas are effectively "deserts" during the winter

months and the shedding of leaves is an adaptation for water conservation. The leaves of

conifers, however, are adapted to cope with limited water in the winter by (1) their

needle shape, which decreases the surface area-to-volume ratio, (2) their sunken stomata

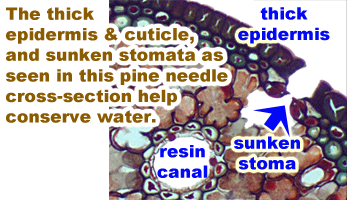

which, being recessed in pits in the leaf surface, lose less water (stomata are the pores

through which plant leaves lose water), and (3) their thick cuticle (a waxy coating) and

epidermis (skin) which act to retard water loss. By keeping their leaves, evergreens are

able to photosynthesize whenever there is sufficient sun and liquid water in the soil,

which means earlier in the spring and later in the Autumn than deciduous plants.

which, being recessed in pits in the leaf surface, lose less water (stomata are the pores

through which plant leaves lose water), and (3) their thick cuticle (a waxy coating) and

epidermis (skin) which act to retard water loss. By keeping their leaves, evergreens are

able to photosynthesize whenever there is sufficient sun and liquid water in the soil,

which means earlier in the spring and later in the Autumn than deciduous plants.

Conical crowns help evergreens reduce snow- and ice-load in winter

But as important as water conservation is, there is another extremely important reason

that most temperate-zone trees are deciduous, and it has to do with snow! I visited

Buffalo, New York one recent October with my girlfriend who is now my lovely wife. Buffalo had

just been hit hard by an unexpectedly deep (2 ft, or 0.6 m), wet and seasonally early

snow. Unfortunately, the deciduous trees such as oaks, cherries, and tulip-poplars had

not yet shed their leaves and, as the snow accumulated on the broad leaves of their broad

crowns, their limbs snapped and some trees split down the middle in catastrophic failure!

Street after street looked like a tornado hit it. The evergreen conifers, however, were

fine, since their narrow needles and strongly conical shape enabled them to shed the

weight of the heavy snow. Thus, most trees lose their leaves in Autumn also to avoid the

mechanical stress of the winter snow and ice.

But as important as water conservation is, there is another extremely important reason

that most temperate-zone trees are deciduous, and it has to do with snow! I visited

Buffalo, New York one recent October with my girlfriend who is now my lovely wife. Buffalo had

just been hit hard by an unexpectedly deep (2 ft, or 0.6 m), wet and seasonally early

snow. Unfortunately, the deciduous trees such as oaks, cherries, and tulip-poplars had

not yet shed their leaves and, as the snow accumulated on the broad leaves of their broad

crowns, their limbs snapped and some trees split down the middle in catastrophic failure!

Street after street looked like a tornado hit it. The evergreen conifers, however, were

fine, since their narrow needles and strongly conical shape enabled them to shed the

weight of the heavy snow. Thus, most trees lose their leaves in Autumn also to avoid the

mechanical stress of the winter snow and ice.